Centro Studi Didattica delle Arte

Via Cartoleria 9

Bologna

www.fondazionecarlogajani.it

Thursday – Sunday, 11:00 – 19:00

free entrance

In December of 2009, Carlo Gajani passed away. His left behind oeuvre is witness of a long successful artistic career. Ten years later, is a good moment to look back to 40 years of artistic practice. Delayed by the Corona-crisis, the retrospective opened on 8 October 2020. Curated by Renato Barilli, the exhibition, presents works by the Bolognese artist in three sections. There are engravings of the first half of the 1960s, a large selection of paintings, dating from the early 1960s to the 1970s and finally photography from the 1980s and 90s. Additionally, there is a video. Students from the supporting Liceo artistico Francesco Arcangeli interviewed the president of the Fondazione Carlo Gajani, Angela Zanotti Gajani. Many oeuvres are provided by the foundation and were last on view in the 1960s.

In December of 2009, Carlo Gajani passed away. His left behind oeuvre is witness of a long successful artistic career. Ten years later, is a good moment to look back to 40 years of artistic practice. Delayed by the Corona-crisis, the retrospective opened on 8 October 2020. Curated by Renato Barilli, the exhibition, presents works by the Bolognese artist in three sections. There are engravings of the first half of the 1960s, a large selection of paintings, dating from the early 1960s to the 1970s and finally photography from the 1980s and 90s. Additionally, there is a video. Students from the supporting Liceo artistico Francesco Arcangeli interviewed the president of the Fondazione Carlo Gajani, Angela Zanotti Gajani. Many oeuvres are provided by the foundation and were last on view in the 1960s.

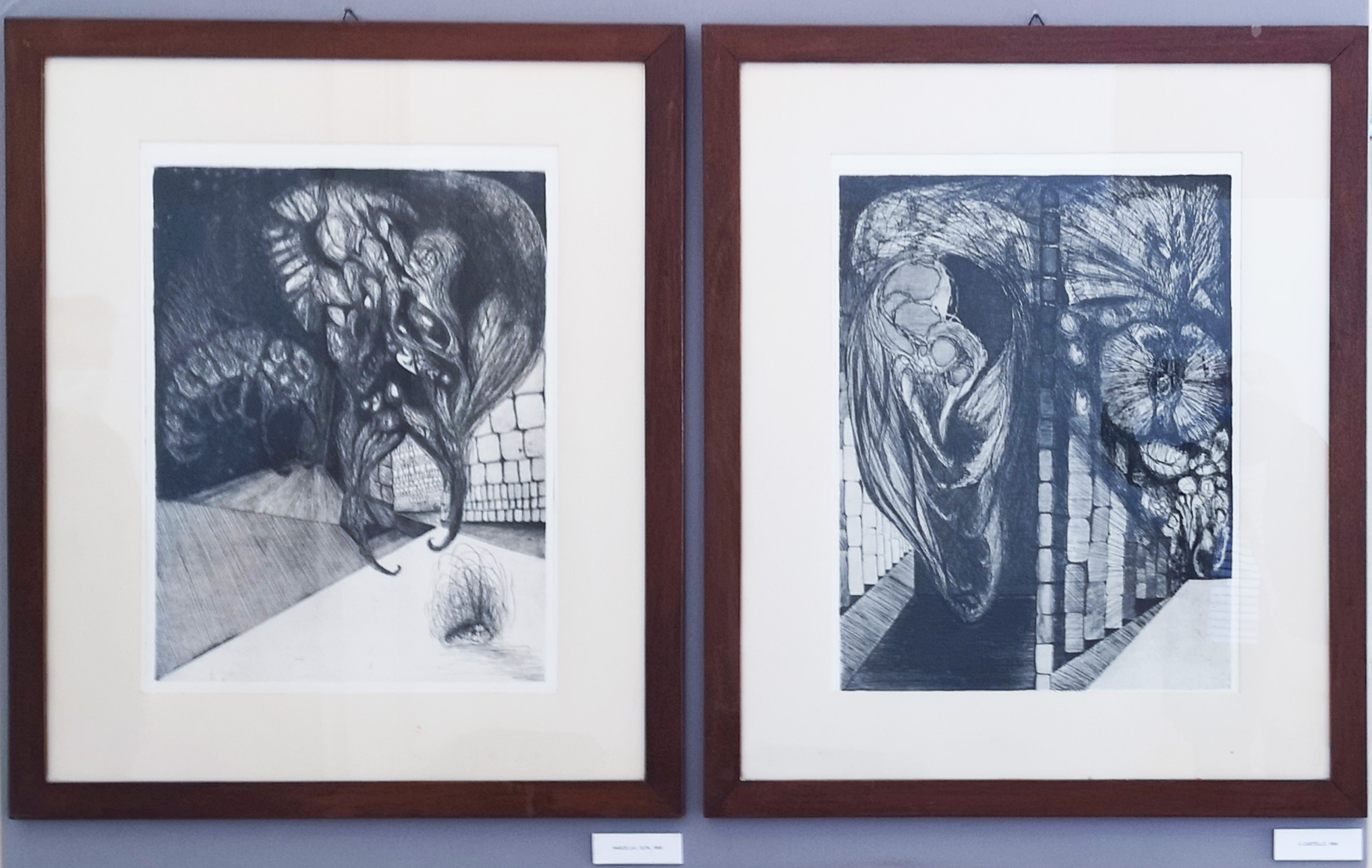

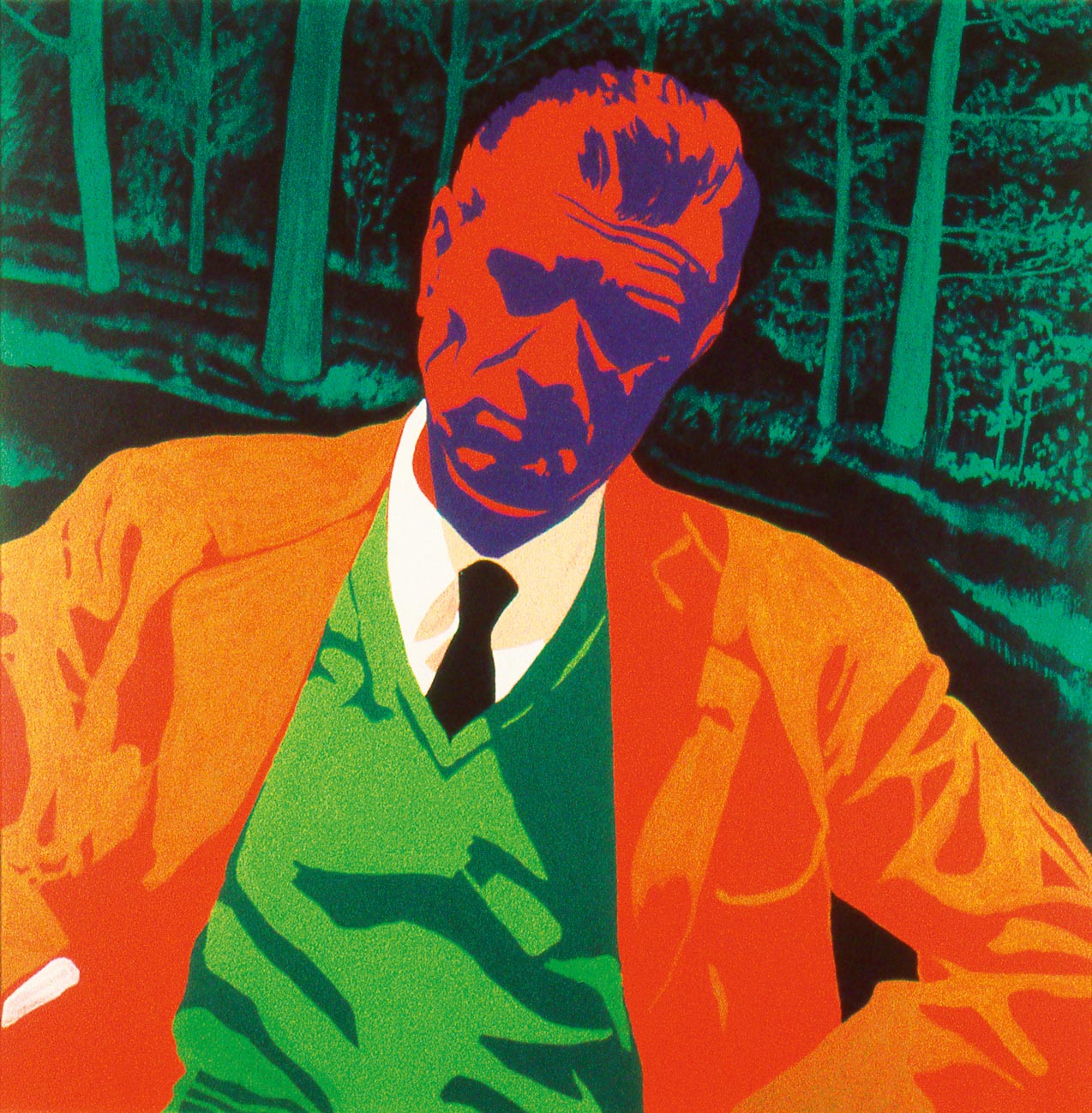

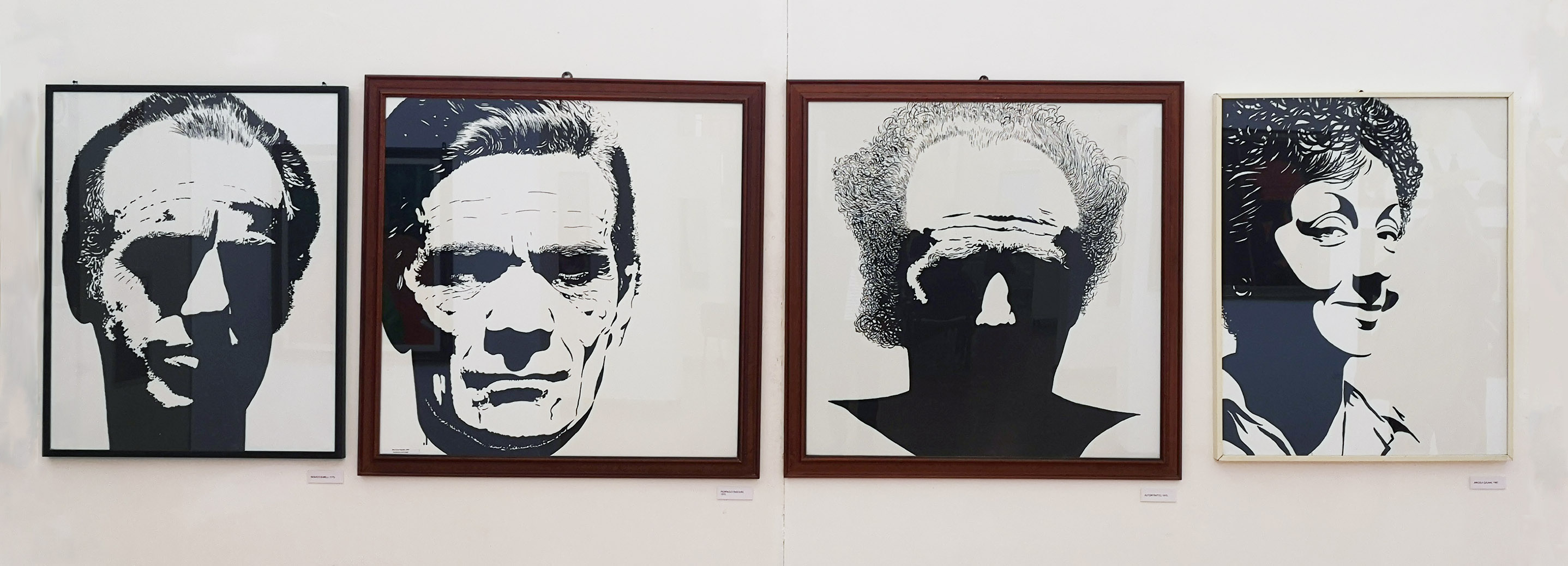

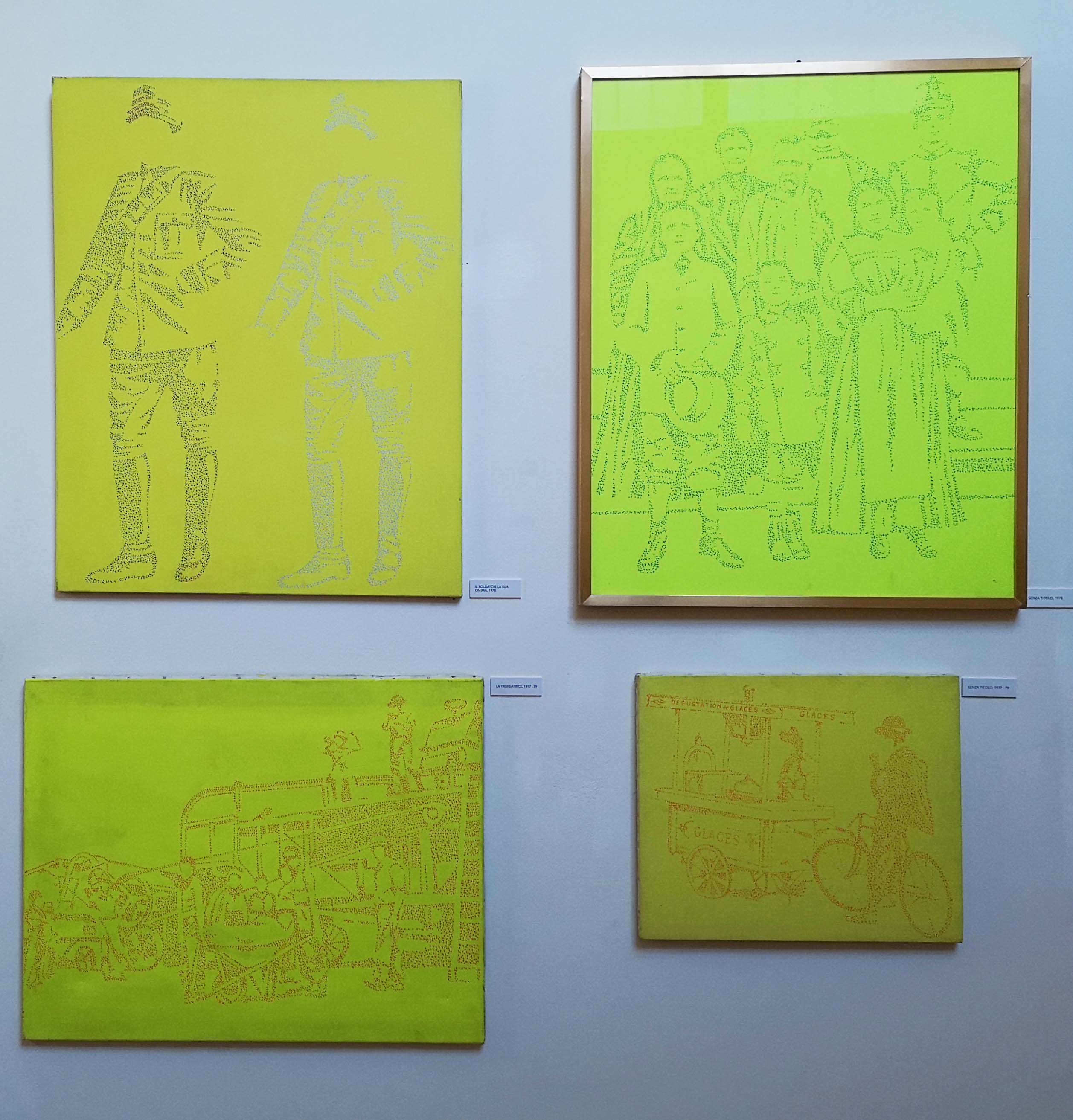

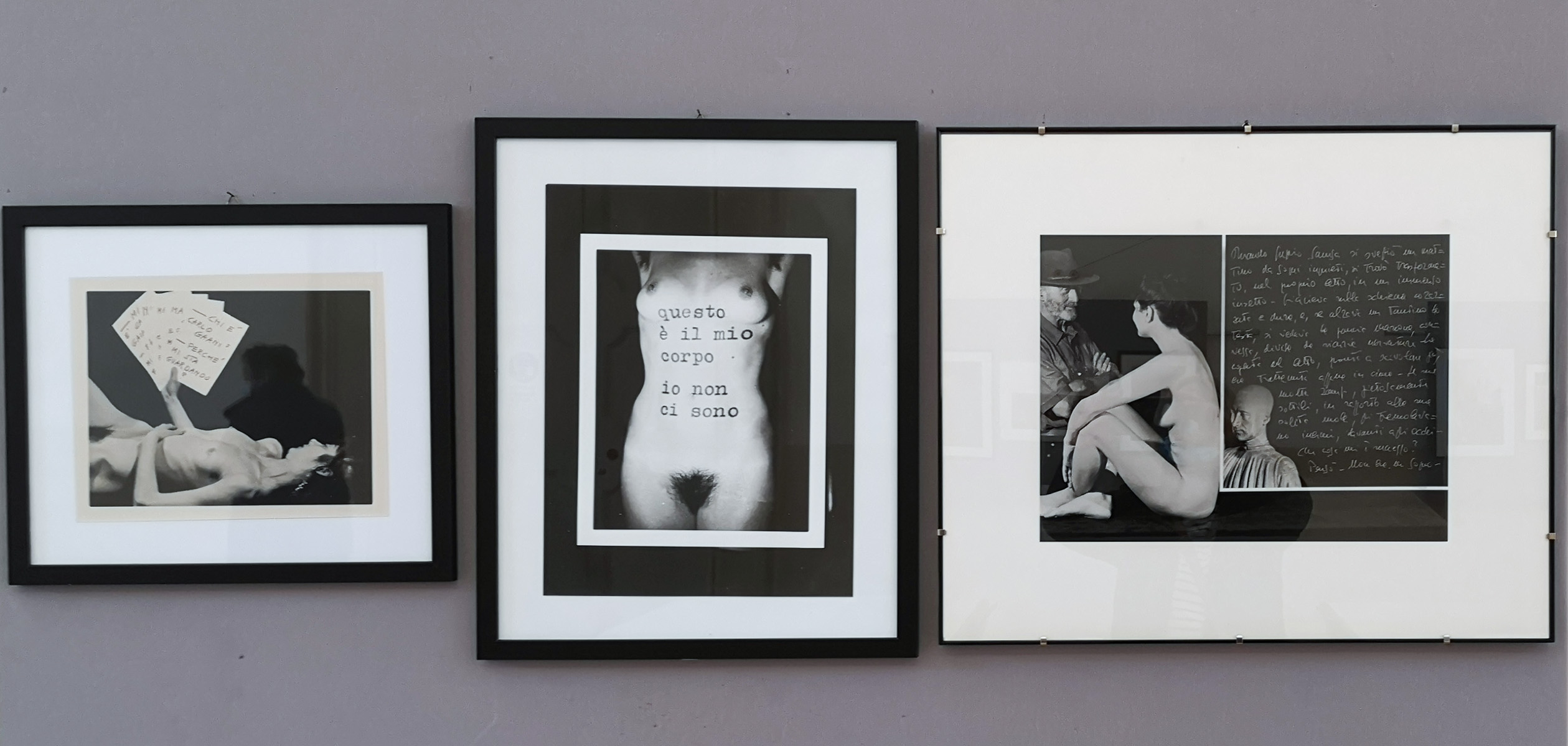

Born in 1929 in Bazzano, Province of Bologna, Italy, Carlo Gajani intended to become a pianist. Unfortunately, an infection caused a unilateral hearing deficiency. Hence, he studied medicine and graduated in 1953. During his nearly 15 years practice as a doctor, he started painting, with a first inspiration by the informal. Besides, he also made engravings. Here, his hardly definable spaces often are populated by strange beings, reminding polyps or internal organs, which he might have known in his time as doctor. Gajani’s paintings developed from abstract in the early 1960s to portrait in the second half of the decade. The influence of Pop Art is obvious, even though the artist established his individual style. While his early coloured portraits in the exhibition are marked by shadowy representations, the ones from the 1970’s are black and white paintings in a photorealistic manner, although the sensation of paper cutting remains. By the time, a gallery of illustrious personalities emerged. Mostly they are from Bologna or are attached to the city, such as Renato Barilli and Pier Paolo Pasolini. His engagement to the problem between portraiture and photography lead to the publication “Ritratto, identità, maschere” (Portrait, Identity, Mask) in 1976. It is on one hand the story of these portraits, but also the discussion of the theoretic problems of photography and the artists’ stylistic solution. Already in 1964 and again in 1972 Carlo Gajani was invited to the Venice Biennale. Maybe this second presentation of his works at this internationally renowned art show contributed to the decision to dedicate his entire activities to art. In 1972, he started to teach artistic anatomy at the Academy of Fine Arts in Urbino and later in Bologna. Apparently, he could not completely escape his medical background. However, in the late 1970’s the artist also started to develop another form of painting, which is orientated to divisionism. The examples in the exhibition are mainly yellow-grounded. On this base, Gajani forms dimly silhouettes by small dots of different colours. Depicted are by the title not identifiable individuals, but rather prototypes like the ancestors, the couple, the soldier or farmers. In the 1980’s the artist changed his medium from painting to photography. Still, he remained faithful to portrait. Compared to the black and white paintings, which reminded cut-outs, the lines are softer by less contrast. Additionally, the background is now black instead of white. The “Self-portrait in the Accademia” constitutes a passage to nude representations, which became another centre of his interest. During 20 years, Gajani explored this genre, always intrigued by the relationship between photographer and model. Moreover, Gajani extended his photographic activity to landscapes. On one hand, there are the exhibited photos of New York as part of his North American urban landscapes. They reveal a sort of return to abstraction. Skyscraper-facades, trees and people are reflected at the glass fronts of other buildings and are deprived of their context. On the other hand, there are the landscapes of the valley of the river Po, which are a search for a vanishing world. Also here, there is a certain tendency to abstraction, regarding the “Houses with Eyes”. The before eminent represented people are completely disappeared in these late works, as if to return to the beginnings.