La Biennale di Venezia 2022

La Biennale di Venezia 2022

23 April – 27 November 2022

The presented artworks in the first part of our article about the Venice Biennale in the Giardini was a glance to the female conditions in society. In the second part, there is a focus on nature and technology, not without including bodies and their place in the world.

Entering the domain of technology

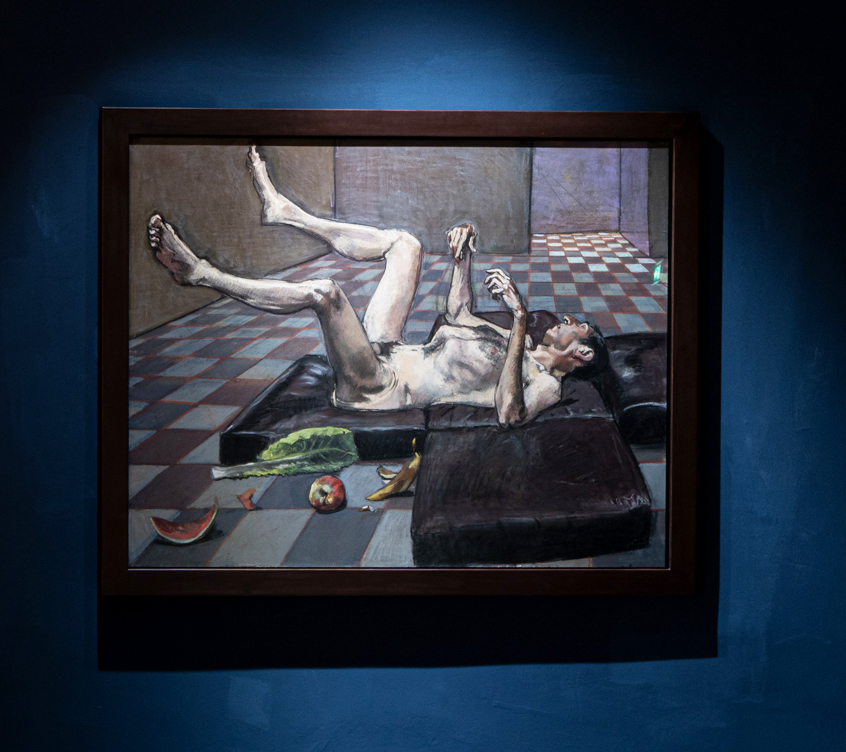

Paula Rego: subjected

An entire room is dedicated to pastels and sculptures of the late Paula Rego. If the before presented paintings often had a surrealistic touch, the paintings here are almost naturalistic. The pictures – most of them of the 1990s – show women and children, often in difficult situations like rape, abortion or infanticide. Portuguese fairy tales inspired Rego’s figurative imagery, but also old masters like Francisco Goya and Honoré Daumier influenced her work. Moreover, literature conduced as bases, for example “Geppetto Washing Pinocchio” (1996) and “Metamorphosing after Kafka” (2002). Since the 2000s, the artist made cloth dolls as a form of sculpture. Her mixed media work “Oratório” (2008-2009), reminds ancient winged altarpieces, although, there are no religious scenes. Oratório combines puppets with paintings and shows once more women in tragic circumstances. Here, the nurse in the middle field recalls a Pietà and the rape on the upper left wing could be inspired by artworks of the rape of Europe. Rego did not hesitate to show the oppression and violence towards woman.

Besides, there are graphic prints from the artists “Nursery Rhymes”, made in 1989 and published as book in 1994. Taking from British poems and songs for children, the artist exaggerated and ironised the scenes.

Entering the domain of technology

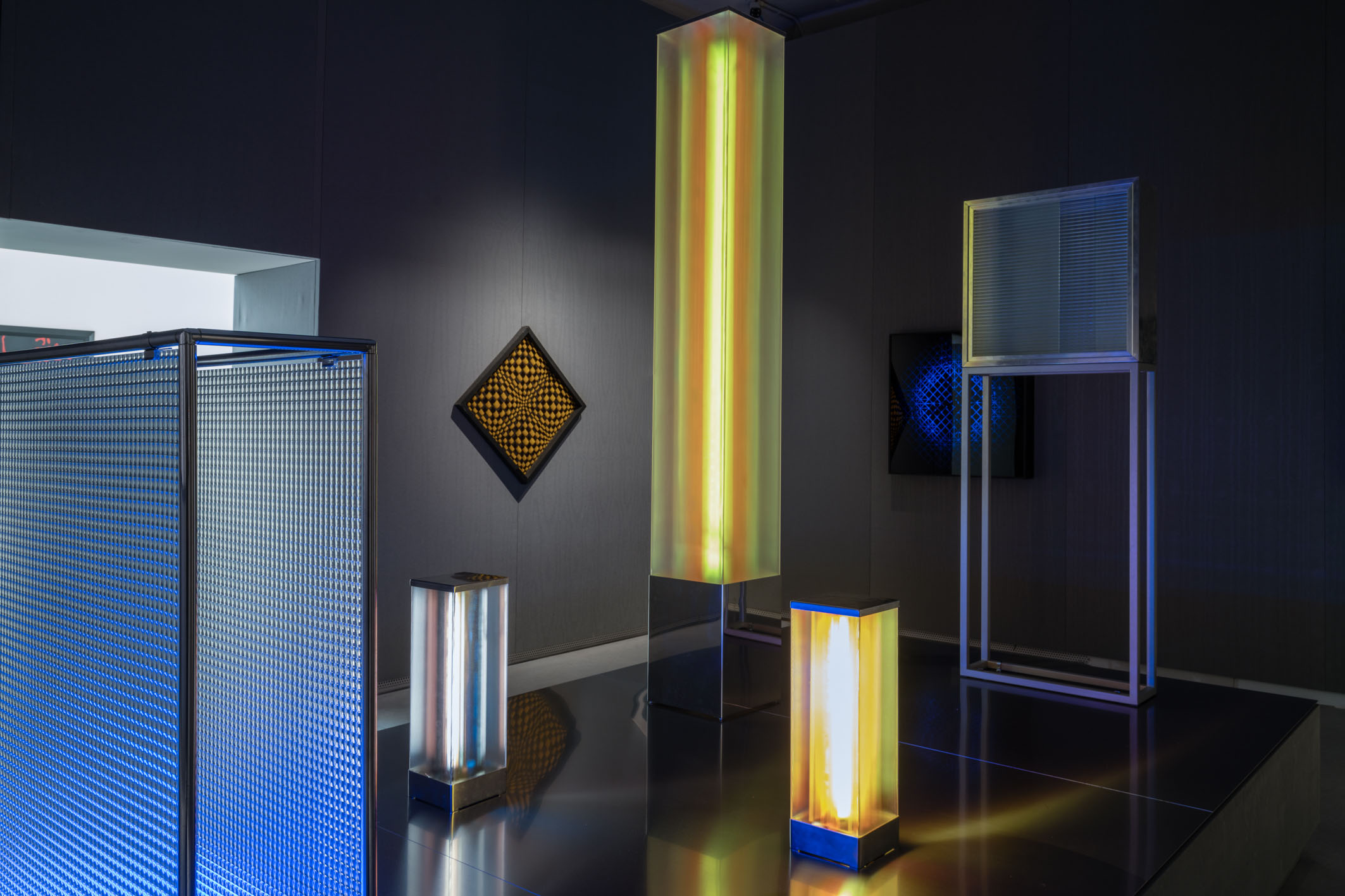

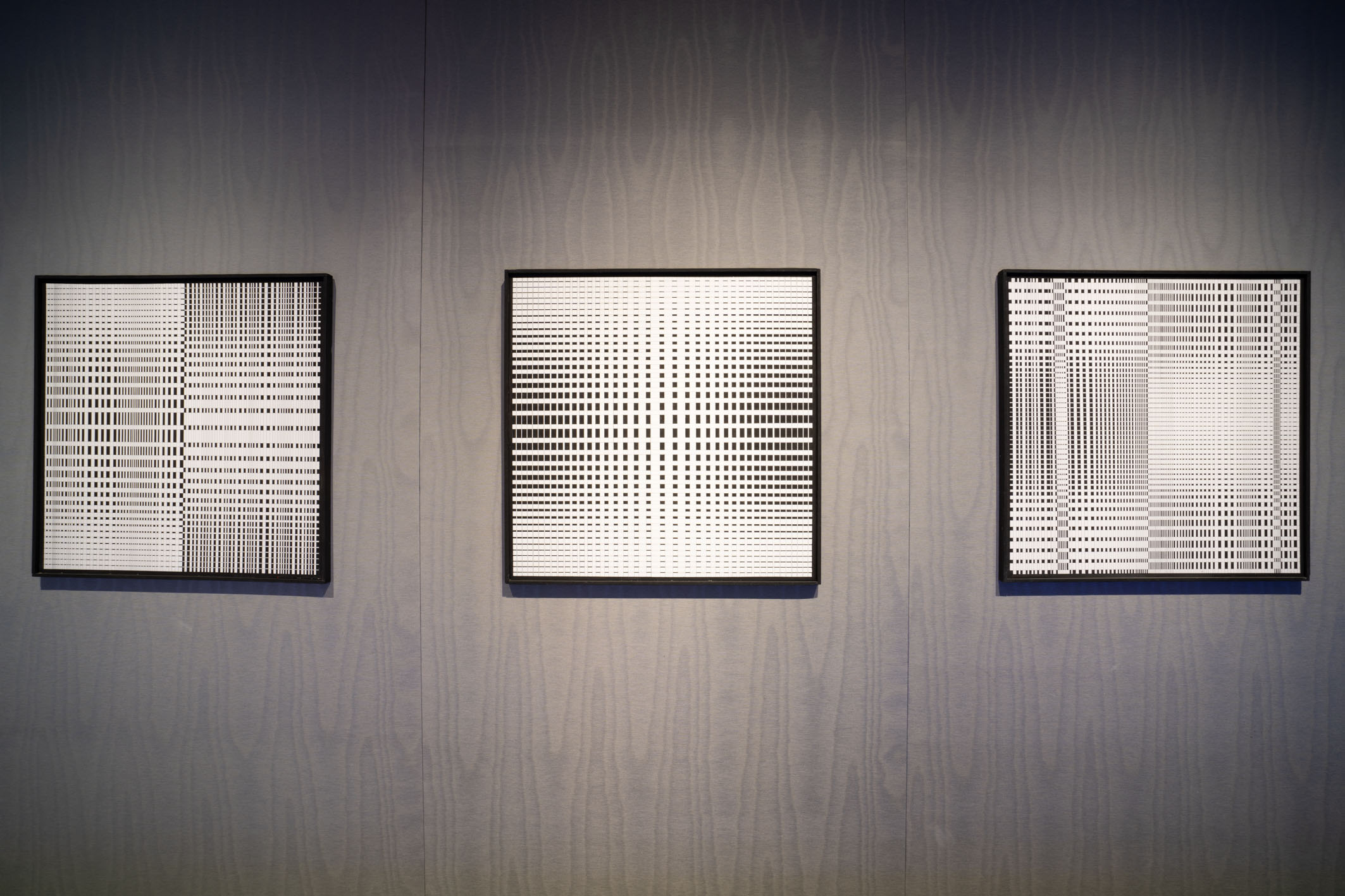

The time capsule “Technologies of Enchantment” is with its six artists rather small. Not surprisingly, since even today women and technology are regarded as a contradiction. Hence, technical professions are still a masculine domain. Nevertheless, in the 1960 also female artists started to include elements of the technical or computerised world into their work. Hereby, the capsule present two directions of this influence: the use of new materials and electricity to create artworks and handmade depictings, which seem to be generated by a computer. All works have in common that they follow the idea of an active contemplator, who moves to perceive the complexity of the artwork.

Grazia Varisco (Schema luminoso variabile R. VOD. LAB, 1964), Laura Grisi (Sunset Light, 1967) and Nanda Vigo (Diaframma, 1968) use light to obtain poetic effects and utilise as framework Plexiglas, steel, aluminium or even wood. Despite the technical approach, there is an effect of magic and sentiment in the creations. Whereas Dadamaino (Oggetto ottico-dinamic, 1960-61), Marina Apollonio (Rilievo 902, 1964-69) and Lucia di Luciano (Irradiazioni N. 9, 1965) generate optical effects by “traditional” painting or relief. More or less two-dimensional objects create the illusion of three-dimensionality, magic!

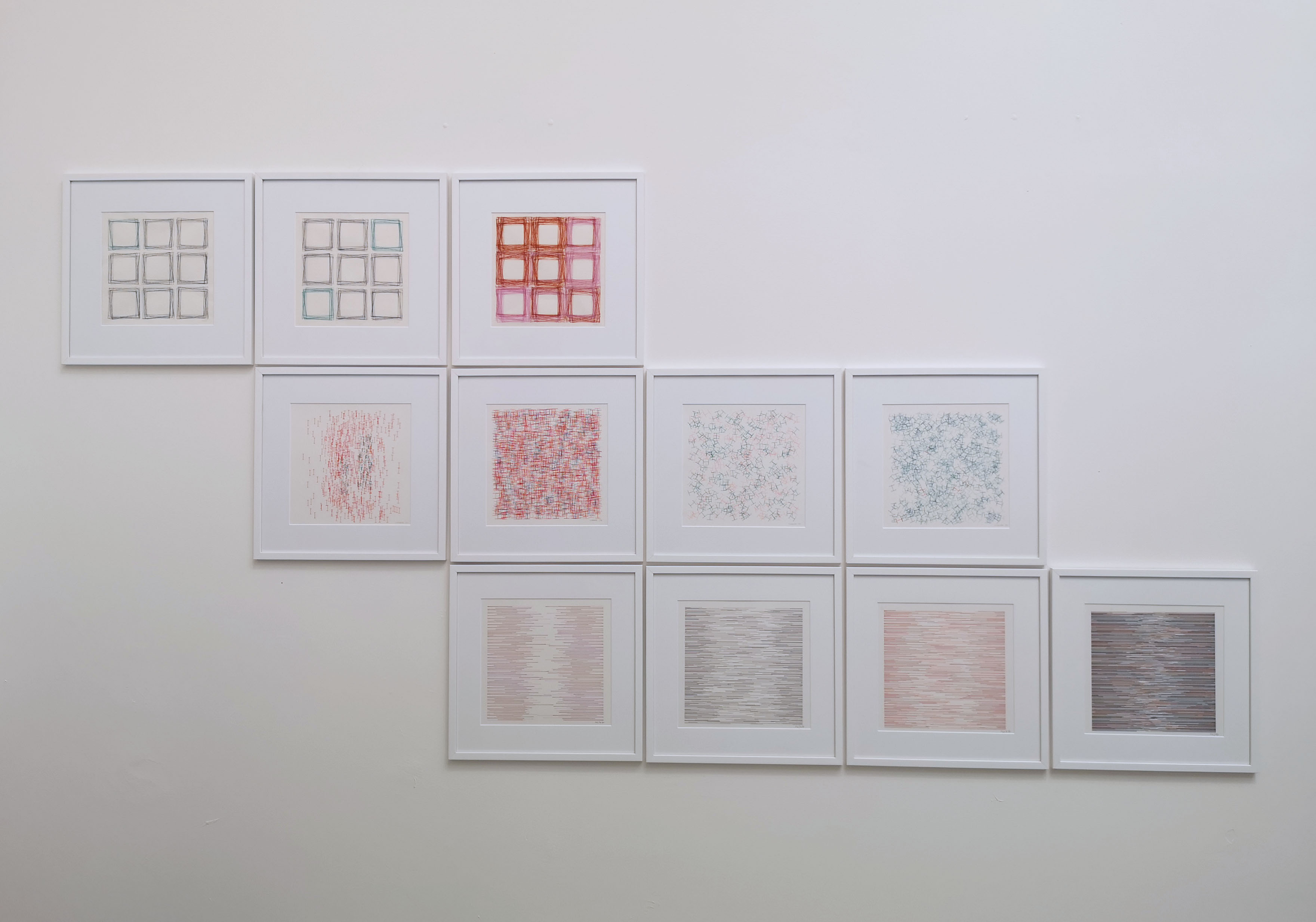

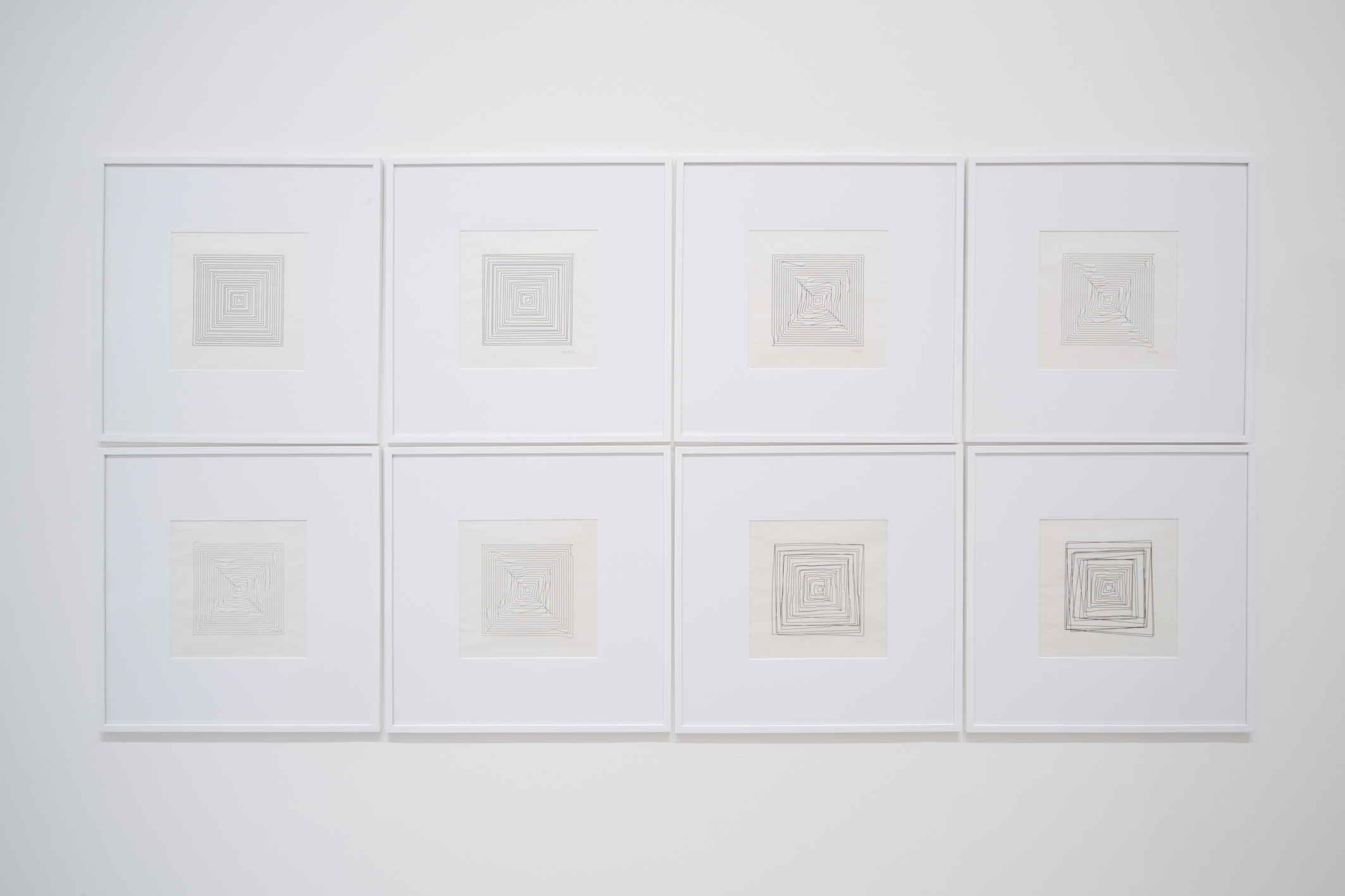

Technology and bodyAlready in the early 1960s, Vera Molnár made paintings, based on logical reflexion. First, she imagined to write a computer program and followed the principals during painting. With this “méthode immaginaire”, she started with squares and points to vary them according to the guidelines, to create series with 1 % disorder. After having developed a software in cooperation with her husband, Molnár switched to computer plotter drawings. Hereby she became a pioneer of computer art. Perhaps therefore, she is not included in the previously described time capsule, but has an individual representation within the main exhibition.

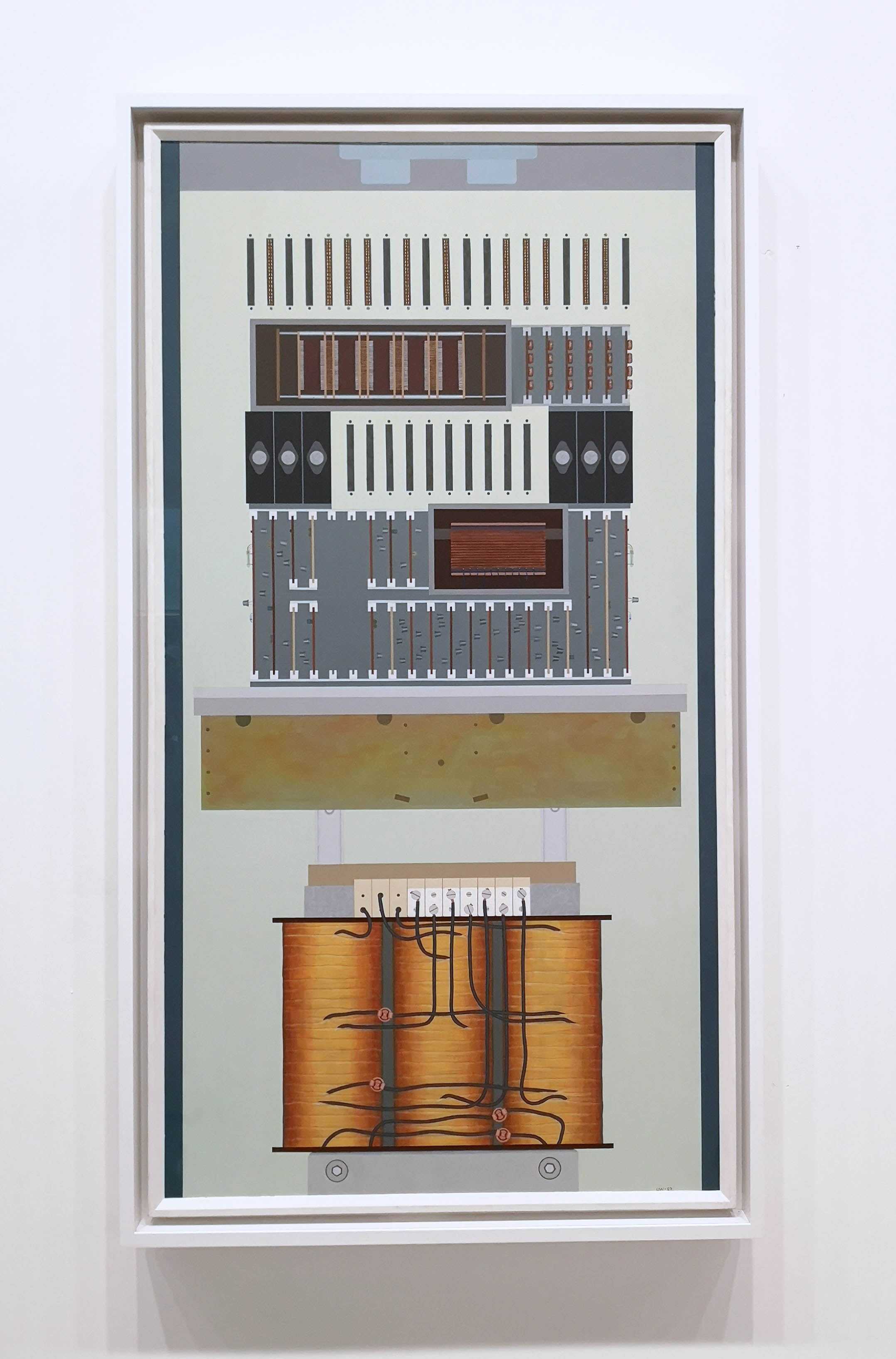

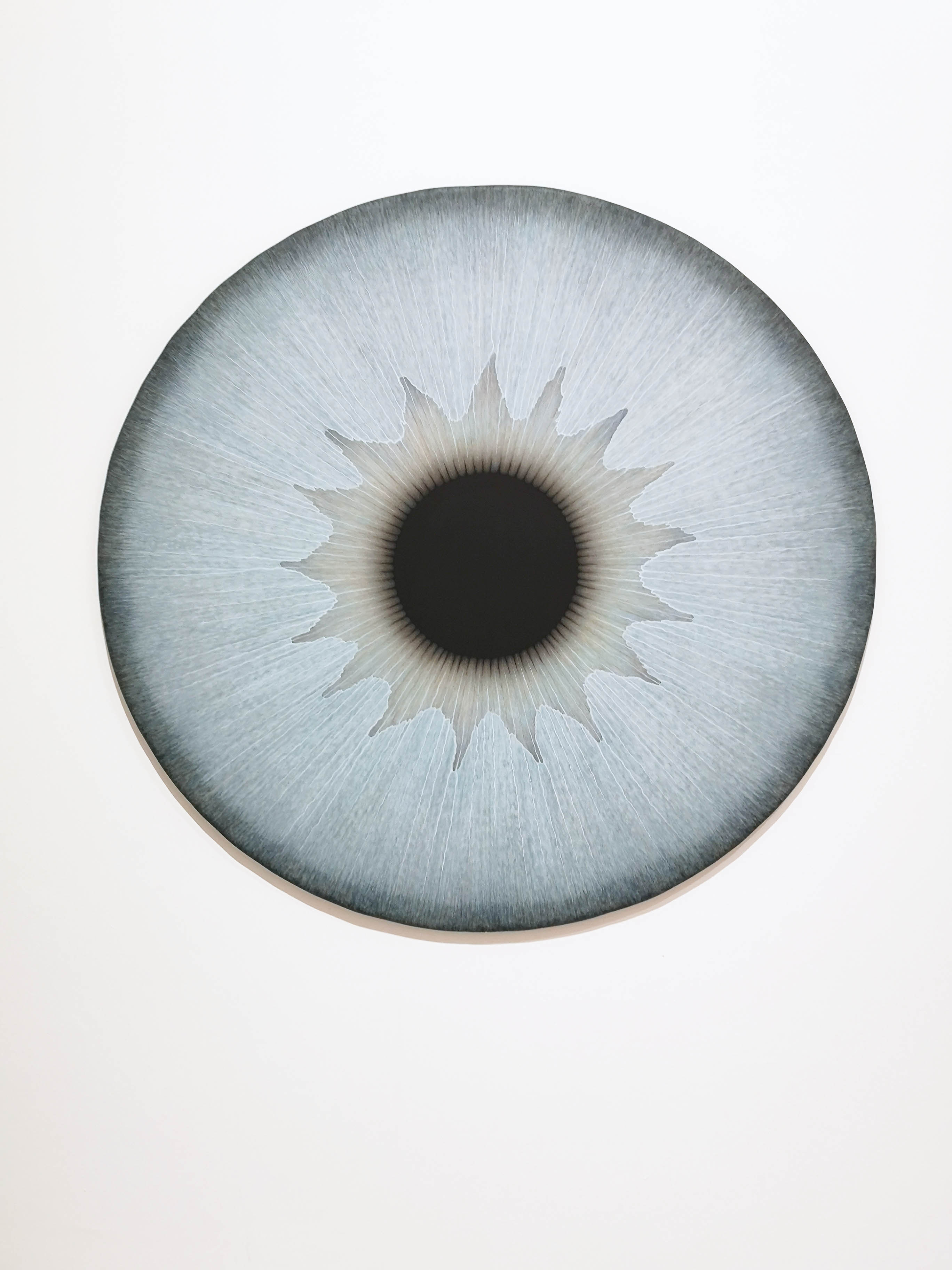

Another approach made the younger Ulla Wiggen. Early in her career, also in the 1960s, she painted circuit boards and electronic bits and in 1967 the TRASK, at this time the fastest computer in the world. Later, the artist turned her attention more to nature, always in a realist style. There was a period with people in landscapes. Then she returned to her more analytic creations, but this time she didn’t point to machines. She depicted brains, hearts and other organs of the human body. Since 2016, Wiggen works on her ongoing series of “Iris Paintings”. Some of them and several early works are on view in the Central Pavilion. Alienation of the bodyAneta Grzeszykowska deals in a very different way with the human body. Her interest is identity and the image of individuals. In her photo series “Mama” (2018), she questions the relationship between mother and daughter. For this propose, she gave her daughter a silicon doll, which portraits the artist herself. In the developing interaction between daughter and model, the child assumed the mother role, in caring for the puppet. She caresses and baths it, undertakes a boat trip, places it on a garden chair and so on. Hereby, the image of the mother became progressively the object of a game so far that the daughter painted the face and finally buried it in the dirt. In contrast to the artists of the first two time capsules, who tried to gain control over their bodies and identity, Grzeszykowska alienates from it and hand it over. This might be interpreted as a critic on the media-orientated society, where human beings and especially women are still deprived from the right of self-determination and where others decide about the image and role of individuals.

In this way, the circle closes. The presented artworks and many others in the exhibition are questioning body, identity and society. Hereby, the artists employ various artistic approaches and techniques, depending on their individual choices. However, they are rarely isolated in the historic context and the current constitution of the society. Cecilia Alemani shows that the artistic accomplishments are interwoven if not influenced by each other. Despite all differences, several of the artist’s concerns appear recurrently. With this female view on the world, she enlarges our horizon considerable.

Text: Astrid Gallinat

Photos © Astrid Gallinat & Stephan Goseberg, if not mentioned otherwise