La Biennale di Venezia 2022

23 April – 27 November 2022

Founded in 1895, the Venice biennale was – until now – dominated by masculine curators and artists. Since 1948, there were 32 male artistic directors and only 3 female. Additionally, there was two times a double curatorship, once a male-female couple, the other one two women.* The art world had to wait 127 years to see its first Venice Biennale with a feminine majority. Under the title “The Milk of Dreams” Cecilia Alemani invited 213 artists with 1433 artworks. Thereof, only 10 % are masculine, the rest are women or gender fluid. Anyway, the show is not a combative feminist manifestation. Rather it is a reflection on feminism, a look at the female perspective on human life, society and female experience in the world. We would like to invite you to a visit of the Central Pavilion in the Giardini of the Biennale, to have a closer look to this exceptional exhibition.

Founded in 1895, the Venice biennale was – until now – dominated by masculine curators and artists. Since 1948, there were 32 male artistic directors and only 3 female. Additionally, there was two times a double curatorship, once a male-female couple, the other one two women.* The art world had to wait 127 years to see its first Venice Biennale with a feminine majority. Under the title “The Milk of Dreams” Cecilia Alemani invited 213 artists with 1433 artworks. Thereof, only 10 % are masculine, the rest are women or gender fluid. Anyway, the show is not a combative feminist manifestation. Rather it is a reflection on feminism, a look at the female perspective on human life, society and female experience in the world. We would like to invite you to a visit of the Central Pavilion in the Giardini of the Biennale, to have a closer look to this exceptional exhibition.

A monumental prelude to “The Milk of Dreams”

The Witch’s Cradle: The female self-assertion

Corps Orbite: Poetry and Image

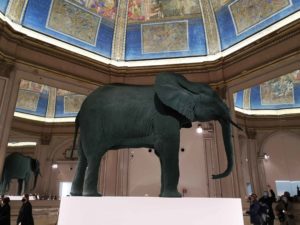

A monumental prelude to “The Milk of Dreams”

The opening sculpture of “The Milk of Dreams” in the Central Pavilion of the Giardini, “Elephant” by Katharina Fritsch seems to come directly of the exhibition’s name giving children’s book by Leonora Carrington. A book, with her drawings of chimeric, fanciful creatures. Life-size and by its detailed elaboration the animal could be almost be vivid, if his colour wouldn’t be green. At the same time, the imposing mammal refers with its matriarchal lifestyle to the concern of the curator to explore a more feminine view on humanity. In the octagonal entrance, the walls are covered with mirrors, so that the sculpture is reflected to infinity. Is this an additional hint to the feminine fertility? However, this underlines the monumentality of the animal and at the same time the ease with which it encircles the visitors.

The opening sculpture of “The Milk of Dreams” in the Central Pavilion of the Giardini, “Elephant” by Katharina Fritsch seems to come directly of the exhibition’s name giving children’s book by Leonora Carrington. A book, with her drawings of chimeric, fanciful creatures. Life-size and by its detailed elaboration the animal could be almost be vivid, if his colour wouldn’t be green. At the same time, the imposing mammal refers with its matriarchal lifestyle to the concern of the curator to explore a more feminine view on humanity. In the octagonal entrance, the walls are covered with mirrors, so that the sculpture is reflected to infinity. Is this an additional hint to the feminine fertility? However, this underlines the monumentality of the animal and at the same time the ease with which it encircles the visitors.

Also in the following hall, the monumentality of the artworks continues. Rosemarie Trockel’s oversized bright coloured “knitting pictures” remind abstract pictures. However, they also refer to the often underestimated work of woman. After being conceived by the artist, a computerised knitting machine generated her first knitting pictures, a collaboration between human and machine. Moreover, they illustrated the alienation of work and the transfer of female handcraft into industrialised work. Whereas the in Venice presented knitting pictures are made by Trockel’s long-time collaborator Helga Szentpétery and signal their hand-made quality. Is this a reconquest of a female domain or/and a metamorphosis in the artists’ work?

Also in the following hall, the monumentality of the artworks continues. Rosemarie Trockel’s oversized bright coloured “knitting pictures” remind abstract pictures. However, they also refer to the often underestimated work of woman. After being conceived by the artist, a computerised knitting machine generated her first knitting pictures, a collaboration between human and machine. Moreover, they illustrated the alienation of work and the transfer of female handcraft into industrialised work. Whereas the in Venice presented knitting pictures are made by Trockel’s long-time collaborator Helga Szentpétery and signal their hand-made quality. Is this a reconquest of a female domain or/and a metamorphosis in the artists’ work?

In choosing these artworks as a prelude to “The Milk of Dreams” Cecilia Alemani refers to the themes and issues raised in the exhibition. Beside others, there are artworks questioning the female role in society, the emancipation from the male image of the female identity and with that, it is the regain. Moreover, there are artistic descriptions of metamorphoses and the recourse to practices beyond rationality. Later, we will see works motivated by the encounter of human beings and technology, which is also already implied in the preamble.

To intensify the examination of the different subjects, the curator introduced five “Time Capsules”. They are exhibitions within the main show, regrouping thematic works by artists and cultural creatives. The presented artworks are coming from different horizons (time, geography, movements) and are intended to offer a historical context to the subjects of the main exhibition.

The Witch’s Cradle: The female self-assertion

In the gallery of the lower level, we enter into the first capsule with the title “The Witch’s Cradle”. Already the presentation in the dimmed room impart an intimate and a little bit mysterious atmosphere, even though the many paper works might have caused the reduced lightning. The title, taken from the unfinished, experimental short film by Maya Deren from 1944, refers to the supernatural origin of many of the artworks in this section. The surrealist influence is undeniable (e.g. Jane Graverol “L’Ecole de la Vanité”, 1967), even though various avant-garde movements are reflected in the practice of the presented artists and cultural practioneers. All the creatives have in common that they knew or even were in close contact to the avant-garde movements. However, they developed their proper style to free themselves from masculine dominance.

In the gallery of the lower level, we enter into the first capsule with the title “The Witch’s Cradle”. Already the presentation in the dimmed room impart an intimate and a little bit mysterious atmosphere, even though the many paper works might have caused the reduced lightning. The title, taken from the unfinished, experimental short film by Maya Deren from 1944, refers to the supernatural origin of many of the artworks in this section. The surrealist influence is undeniable (e.g. Jane Graverol “L’Ecole de la Vanité”, 1967), even though various avant-garde movements are reflected in the practice of the presented artists and cultural practioneers. All the creatives have in common that they knew or even were in close contact to the avant-garde movements. However, they developed their proper style to free themselves from masculine dominance.

Besides film sequences from Maya Deren, there is – self-evident – a painting by Leonora Carrington. To discover or rediscover are twelve drawings from Toyen (Marie Čermínová) from 1939/40. In the “The Shooting Gallery” the artificialist depicts a post-war scenario, where humans have disappeared, only animals, doll-like creatures and mannequins “survived”. Contrasting to this is the body-accentuating performance of Josephine Baker, a woman, which not only overrun social and racial borders, but also freed her own body against the conventions of her time. Therefore, the Witch’s Cradle might also refer to the fact that these women resisted the masculine influence on their lives, body and creativity. Like savant and independent women in the middle ages, they were often penalised. Even though, in the 20th century women were no longer burned to death, but disregard and neglection often prevented their representation in common art histories.

Besides film sequences from Maya Deren, there is – self-evident – a painting by Leonora Carrington. To discover or rediscover are twelve drawings from Toyen (Marie Čermínová) from 1939/40. In the “The Shooting Gallery” the artificialist depicts a post-war scenario, where humans have disappeared, only animals, doll-like creatures and mannequins “survived”. Contrasting to this is the body-accentuating performance of Josephine Baker, a woman, which not only overrun social and racial borders, but also freed her own body against the conventions of her time. Therefore, the Witch’s Cradle might also refer to the fact that these women resisted the masculine influence on their lives, body and creativity. Like savant and independent women in the middle ages, they were often penalised. Even though, in the 20th century women were no longer burned to death, but disregard and neglection often prevented their representation in common art histories.

Corps Orbite: Poetry and Image

In the room adjoining, we enter into the next time capsule. “Corps Orbite” mainly reunites artists working in visual or concrete poetry in an extended sense. Herewith, it refers to the exhibition “Materialisazzione del linguaggio” curated by Mirella Bentivoglio in 1978 as part of the 38th Venice Biennale. At the time, some critic ironized the show as “pink ghetto”. Fortunately, also in the art world the situation has changed, even though we are still far from gender equality. However, some of the presented artists are recognised in the canon of recent art history. While Tomaso Binga has chosen a masculine alias for her artistic career in 1977, most of the female artists work under female names.

In the room adjoining, we enter into the next time capsule. “Corps Orbite” mainly reunites artists working in visual or concrete poetry in an extended sense. Herewith, it refers to the exhibition “Materialisazzione del linguaggio” curated by Mirella Bentivoglio in 1978 as part of the 38th Venice Biennale. At the time, some critic ironized the show as “pink ghetto”. Fortunately, also in the art world the situation has changed, even though we are still far from gender equality. However, some of the presented artists are recognised in the canon of recent art history. While Tomaso Binga has chosen a masculine alias for her artistic career in 1977, most of the female artists work under female names.

The time range of the creations spans the 19th and 20th century. But these artworks are not at all only carmina figurata or word pictures. Most of all, remind Tomaso Binga’s “Dattilocodice” (1978) and Giovana Sandri’s “Costellazione di lettere” (1977) to concrete poetry, even though, the two women developed her own conceptions. The first combines letters and numbers to juxtapose them; the second forms an image, which might recall word pictures, though it is more a graphic constellation. Herewith, we approach depictive representations and actually, there are several examples in this direction.

The time range of the creations spans the 19th and 20th century. But these artworks are not at all only carmina figurata or word pictures. Most of all, remind Tomaso Binga’s “Dattilocodice” (1978) and Giovana Sandri’s “Costellazione di lettere” (1977) to concrete poetry, even though, the two women developed her own conceptions. The first combines letters and numbers to juxtapose them; the second forms an image, which might recall word pictures, though it is more a graphic constellation. Herewith, we approach depictive representations and actually, there are several examples in this direction.

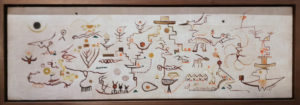

Alice Rahon was inspired by ancient cave paintings and included prehistoric signs, which she painted with oil on canvas (Thunderbird, 1946). With Gisèle Prassinos returns the figurative, even though, the depicted persons have a strong character of signs in “Portrait de famille” (1975). Here she recounts the story of a family with a patriarchal dominating father, who is challenged by his daughter.

Alice Rahon was inspired by ancient cave paintings and included prehistoric signs, which she painted with oil on canvas (Thunderbird, 1946). With Gisèle Prassinos returns the figurative, even though, the depicted persons have a strong character of signs in “Portrait de famille” (1975). Here she recounts the story of a family with a patriarchal dominating father, who is challenged by his daughter.  Herewith Prassinos describes the world as it is, without regulation from outside. This is the common interest of the presented artists in “Corps Orbite”: liberation from masculine guidelines and creation of their own language. Despite her formal traditional poetry, Joyce Mansour is very successful in her way. In her book “Les Damnations” (1966, illustrated by Roberto Matta) she uses an unfiltered language, not afraid to describe sexual instincts, knowing how to handle them. Thus, she drew an image of an emancipated woman, which is neither femme enfant nor femme fatal.

Herewith Prassinos describes the world as it is, without regulation from outside. This is the common interest of the presented artists in “Corps Orbite”: liberation from masculine guidelines and creation of their own language. Despite her formal traditional poetry, Joyce Mansour is very successful in her way. In her book “Les Damnations” (1966, illustrated by Roberto Matta) she uses an unfiltered language, not afraid to describe sexual instincts, knowing how to handle them. Thus, she drew an image of an emancipated woman, which is neither femme enfant nor femme fatal.

In the second part about “The Milk of Dreams” in the Central Pavilion of the Giardini, we will encounter a third time capsule “Technologies of Enchantment”. Some artworks of the main exhibition refer in part to the new tools, others return to the role of the human body.

In the second part about “The Milk of Dreams” in the Central Pavilion of the Giardini, we will encounter a third time capsule “Technologies of Enchantment”. Some artworks of the main exhibition refer in part to the new tools, others return to the role of the human body.

Text: Astrid Gallinat

Photos © Astrid Gallinat & Stephan Goseberg, if not mentioned otherwise